This essay is pretty far outside my usual beat of niche biology topics, but I thought it was important. If you find it boring or distasteful, don’t worry, I don’t intend this to be a regular thing.

To start off with, I’d like to say that I am very sympathetic to effective altruism (or EA, for short) and its goals. Both the philosophy and the community have had a big impact on my life and my business. I also think EA would definitely be a beneficial force in American politics, which sorely needs good people.

All of this this is why it makes me so sad that EA has just spectacularly fumbled its first foray into electoral politics.

Now, if you’re not up to date on current US politics, the Effective Altruism community has just blown about $14 million on the Carrick Flynn campaign, including $7-$11 million (numbers vary) from Sam Bankman-Fried, the effective altruist crypto billionaire. Carrick Flynn is a guy with impeccable effective altruist credentials and very little political experience who ran in the Democratic primary for a newly created House seat in Oregon. He lost to Andrea Salinas, a longtime local Democratic political operative in that area, albeit one who never ran for election. She, needless to say, did not spend $14 million on her campaign.

$14 million would have been a lot of money to spend on Flynn’s campaign even if he had won, as it’s difficult for any Congressperson to make a difference in today’s government, nevermind an incredibly junior Congressman with no political experience.

Considering that Carrick lost, it’s, well, a shitton of money. I don’t want to bring up the whole bednets thing, but $14 million buys a lot of bednets.

If the EA community plans to have political influence/run candidates in the future, I think there needs to be a much better plan than what there was for Carrick, which mostly seemed to be “EA guy decides he wants to run, everyone gives him money”. After all, this is supposed to be a rational community, and that doesn’t seem like a particularly rational strategy.

This essay is an attempt to develop the frameworks of that plan. It’s based around Dominic Cummings’ long, detailed, somewhat rambling blogs (1, 2, and 3) on how he thought out the Leave Campaign for Brexit, which was a very well-run campaign that accomplished its goals despite a lot of structural disadvantages and starting very far behind in the polls. It’s filtered through my experience selling stuff: although I’ve never run a campaign, I’ve been self-employed my whole life, selling my services, products, and software to the consumer world at large. I’m pretty good at selling a story, in other words.

Of course, neither my sources nor my own background are perfectly fitted to this task. There will definitely be gaps and errors in this document. I hope to get input from more knowledgeable people to fix it.

But, I just have to say, when I say more knowledgeable, I mean people who’ve actually participated in running a campaign, not people who are “political junkies” or pundits. As someone who’s done a lot of combat sports in my life, I am very aware of how ineffective combat sports fans are once they get punched in the face. I have to assume the same is true of political fans once they actually have to make a decision.

1. Campaigns don’t make waves, they ride them.

One of the most important things that Dominic Cummings harps on is the fundamental idea above: campaigns don’t make waves, they ride them. I’ve also heard this as “The art of being a politician is to find a parade, start marching at the head of it, and then claim you’re the leader”.

In Dominic Cummings’ Leave Campaign, his polling that voters were already concerned about immigration from the EU into the UK, and so one of the main focuses of their messaging was the idea that 58 million Turks were going to join the EU and migrate to the UK, taking jobs and straining the National Health Service. To be clear, this was not the issue that Dominic Cummings most cared about. If you read his writing, he was much more concerned about issues of political control between the EU and the UK. However, he knew it was the issue the voters cared about, so he rode that wave.

Carrick Flynn had 3 issues he cared about listed on his website: fix Congress (i.e. working with anybody to get issues passed), building a green economy, and preventing pandemics. Now, these are worthy issues, in my opinion. However, my opinion doesn’t matter. The real question is: are these worthy issues in the voters’ opinions?

Nope! I don’t even have to justify that by looking at surveys. Most of the reason that EA people were excited about Carrick Flynn was because he was going to make pandemic prevention an issue in Congress. Now, why do you think the other Democrats (or Republicans) haven’t made it an issue in their own campaigns? Because they already know that voters don’t care. Other campaigns aren’t stupid: if voters cared about pandemic prevention, the politicians would talk about it. Voters don’t, so they won’t.

Carrick Flynn should not have made pandemic prevention one of his major issues in his campaign. It would have been a much better idea to talk about issues that Democratic voters care about in his campaign (i.e. the boring culture war stuff that MSNBC talks about endlessly), and then quietly work on pandemic prevention once he got to Congress.

Instead, however, he tried to make his own wave: make the voters care about pandemic prevention, then be the leader in the campaign on that niche issue. This never, ever works.

2. Make sure you pick the right people for the spotlight.

One of Dominic Cummings’ major tasks as the leader of the Leave Campaign was to keep the wrong people out of the spotlight. The most important person that Dominic Cummings had to keep out of the spotlight was Nigel Farage, who was the leader of the UK Independence Party. Even though Farage would be the natural face of the Leave Campaign, given his leadership of a party devoted to the UK leaving the EU, Cummings knew that Farage and UKIP were seen by the public at large as far-right thugs. Cummings describes in his polling how many of his respondents would actually agree with his messaging around Leave, but would refuse to support them because they didn’t want to be seen as in alignment with “those sort”.

Now, let’s turn to Carrick Flynn. I don’t know Carrick Flynn, but from reputation and from what I’ve read he seems like an exemplar of EA values: fiercely smart, devoted to the good of others (often in foreign countries), and very cerebral. He’s probably a great guy to know.

However, he is almost certainly not the right candidate for Oregon’s 6th congressional district. Most obviously, he’s not part of the district and hasn’t been for a long time. He left and did EA stuff all around the world, and literally only came back to run a Congressional campaign. Nobody in the district knew who he was, including any of the local politicians.

But also, according to Wikipedia, Oregon’s 6th congressional district’s two primary industries are agriculture and logging. Now, if I had to pick the guy who would click most with farmers and loggers, it’s not a cerebral nerd.

This also applies to Sam Bankman-Fried. The fact that Sam Bankman-Fried donated $7 million to Carrick Flynn’s campaign became the major focus of the press on Flynn’s campaign. It makes a lot of sense to me, personally, why he did this. Sam Bankman-Fried cares about pandemic prevention, and he wanted to donate to a candidate who also does. However, from the locals’ perspective, “random crypto billionaire donates millions to dude we’ve never heard of who’s running for Congress” is pretty sketchy, and was not helped by the additional EA people donating additional millions to Carrick Flynn.

3. Have a couple focus-tested messages and stick to them.

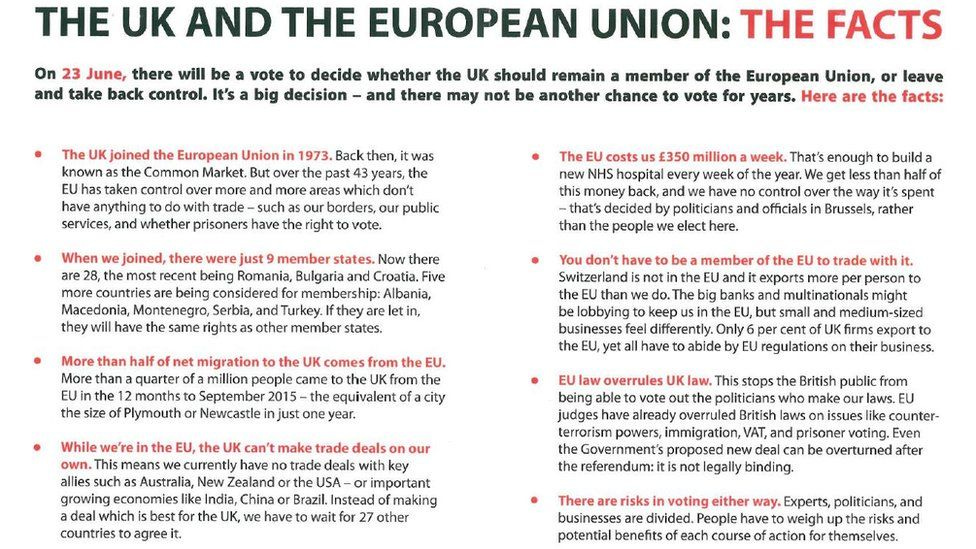

One of the things that Dominic Cummings repeats endlessly is the importance of the Vote Leave campaign’s two central messages:

a) The UK gives 350 million pounds a week to the EU, when they could have been giving that to the NHS.

b) There is going to be a flood of immigration into the UK with the new countries, like Turkey, joining the EU.

They developed these messages near the beginning of the campaign, tested them with a variety of focus groups, and found they were by far the strongest messages. So, those were the messages they stuck to in all of their advertising, public messaging, and media campaigns.

It’s important to note that these were not the most obviously important messages. Dominic Cummings, as previously mentioned, cared most about issues of political control. The media thought that Vote Leave should make their argument about the EU market, and tried to encourage them in that direction in debates. The conservative politicians came up with “Go Global” along with a fun diagram of a globe, which they thought was very clever.

But none of those messages tested as well as Turkey/NHS/£350 million, so Dominic Cummings ignored them.

In Carrick Flynn’s campaign, it seems really obvious that his messages were not focus-tested. In a Democratic primary in an agricultural district, I’d assume that the messages that are going to play best to the Democratic base are going to be either culture war or stuff about supporting agriculture. I would really doubt that messages about effective cooperation or pandemic prevention test well.

Meanwhile, Andrea Salinas, the winner of the OR-06 primary, was focused very deliberately on culture war stuff in her messaging: universal healthcare, $15 minimum wage, abortion rights, and gun control. I’m not saying this is brilliant, but, if you had to bet without doing focus testing on what’s going to be the best message to communicate with a Democratic base, I’d bet it’s the same stuff that gets AOC all of her positive press.

4. Measure the effectiveness of advertising.

As someone who sells my services and products every day for a living, I am forced to be aware of how ineffective most advertising is. I have spent dozens of hours and spent thousands of dollars on ad campaigns which had zero results on my sales.

This is something that Dominic Cummings and his team were also acutely aware of. They only had 13.7 million pounds (coincidentally, close to the amount that Carrick Flynn had) to convince an entire country to vote a certain way. So, when they purchased advertising, they prioritized advertising whose effectiveness could be measured and compared, namely digital advertising (i.e. Facebook ads) and leafleting. They also used follow-up surveys of voters to determine how the advertising changed their likelihood of voting Leave.

Now, I don’t know if Carrick Flynn’s campaign did something similar. But, given that they had $14 million to quickly spend on a district of around 500k people, I’d bet they didn’t. Instead, I’d bet they went the overfunded startup mode: when you have too much money, not enough people to really monitor the money spent, and a limited amount of time to spend the money, you just blanket the ads everywhere and hope for the best. This is not a good way to ensure votes.

Thanks for reading my newsletter! Future posts will almost certainly not be about politics.✓

For what it’s worth, after coming up with his campaign’s messaging, Cummings found the most effective marketing was face-to-face, followed by texts, followed by targeting Facebook ads and targeted mail (including personally addressed mail). Emails and phone calls were almost useless, and Twitter was exceptionally useless.

5. Distract the useless people.

One of Dominic Cummings’ major complaints about the broader Vote Leave coalition was how useless most of his political allies were. Most politicians, in his view, would rather lose a campaign conventionally than win it unconventionally, so they were constantly bombarding him with useless ideas about what they thought should work. This included using the same tactics, consultants, and messaging that had made Vote Leave so unpopular in the start of the campaign.

Cummings’s response was to organize committees for them to be on and then ignore the recommendations of the committees. When he needed them to fall in line (e.g. go on TV and say a certain message), there was a lot of bullying, cajoling, and bribing he needed to do as well.

I’m sure Carrick Flynn, and any person who attracts a lot of EA support, is going to get a lot of well-meaning but useless feedback from EA people, including people in the EA hierarchy. I don’t know how Carrick handled this, but committees seem to be a good way of doing so.

6. Advertise closer to the end of the decision.

This one’s pretty straightforward, but it makes sense. Even though the Brexit referendum was announced many months before it actually happened, Dominic Cummings saved most of his advertising and messaging for the last 10 weeks. Most people don’t think about politics that much or that often, so they really only care close to when they need to make a decision.

7. Decentralize your decision-making

Campaigns are an unwieldy mix of volunteers and paid staff, all of whom are brought on very quickly. It’s like working at a startup with worse incentive alignment. As such, decisions from the top are not necessarily going to be executed at the bottom, and information from the bottom is not necessarily going to be filtered up to the top.

The most important thing, then, is to give everyone the information they need to do their job, and then the latitude to make the decisions necessary as they see fit. This is especially important when it comes to volunteers, who have a wide range of effectiveness, from the incredibly engaged to the half-assed. It’s important for the incredibly engaged to be able to go above and beyond with their work, and not be blocked by the half-assed.

EA and EA-associated political campaigns will of course have this exact issue in spades. Decentralizing and empowering the more engaged so that they aren’t distracted by the less engaged will be huge for making a more effective campaign. I don’t know how Carrick Flynn ran the internals of his campaign, but I hope future EA campaigns go by this model.

8. With a gentleman, a gentleman-and-a-half. With a pirate, a pirate-and-a-half.

This charming phrasing comes directly from Dominic Cummings. If you’re confused about the meaning, it’s basically tit-for-tat: if someone treats you nicely, treat them nicely. If someone treats you poorly, treat them poorly.

I imagine the extent to which this applies in politics would come as a surprise to most EA people. As Dominic Cummings found out, many people who are supposedly on your side in politics will actively work against you for their own reasons. Nigel Farage, for instance, undermined the Vote Leave campaign among his followers, forbidding them from working with Cummings, as he was upset that the campaign did not feature him. This was one of the reasons why Cummings constantly sidelined Farage and refused to give him information.

Carrick Flynn got a taste of this with his owl dustup, in which he said he had “emotional sympathy” for Timber Unity, a group which was frustrated with restrictions on logging due to protections for an endangered owl species. This relatively innocuous phrase of “emotional sympathy” earned this public response from 6 different environmental groups in Oregon:

As organizations who have been fighting for decades to uphold the strong environmental values held by the people of Oregon, we are stunned and deeply saddened to hear Carrick Flynn, a Democratic candidate running for Congress, make comments mocking critical environmental protections, sympathizing with a far-right group that has ties to the Jan. 6 insurrection, and referring to our state’s iconic land use system as ‘insane’.

Carrick Flynn might have expected environmentalists to be gentlemen, at least to him, given that one of his main campaign issues was building a green economy. He was wrong. They were pirates, and he needed to treat them as such. That included not apologizing or reversing statements: pirates take that as a sign of weakness.

9. If you want to get the atypical voters involved, you have to be creative.

EA, by its nature, is a niche philosophy. However, I suspect that there are many non-engaged voters who would be interested in voting for an EA candidate speaking about EA issues, like pandemic prevention.

The challenge is reaching these voters. They are, by definition, not into politics. This was the same challenge Dominic Cummings faced. He wanted to reach working-class men who’d be most affected by a wave of unskilled immigration into the UK. However, these are not the sort of men who are generally into politics. The only news they follow, generally, is football (soccer) news.

So, in order to reach them, that’s exactly the avenue that Dominic Cummings went down. The Vote Leave Campaign did a contest where football fans could win 50 million pounds if they successfully predicted the winner of every game in the European Championships that year. All they had to do was put in their name, address, email, telephone number, and how they intended to vote in the referendum.

Now, what does the European Championships have to do with Brexit? Very little! But that didn’t matter. The important thing was that this information gave Dominic Cummings the information he needed to target the voters.

I’m not sure what the equivalent contest would be for EA. There would need to be some better polling on who’s most sympathetic to EA issues. Perhaps it’s college students, or even churchgoers. However, it’d be easy enough to figure out, and then getting the information for these sorts of voters would only be a stupid contest away.

10. Know what the press cares about.

For the most part, the press was hostile to Vote Leave. When they did cover it, they covered it unsympathetically. More importantly, however, they weren’t particularly interested in covering the issues that Vote Leave cared about, which made it difficult for Vote Leave to get press coverage.

This isn’t unique to Vote Leave. The press, by and large, isn’t interested in substantial coverage of issues, and neither is their readership. When they cover politics, they’re really most interested in the personalities and the drama behind it, or, as Cummings puts it, the “snakes and ladders of careers”.

So, the story that Cummings gave to the press was that Conservatives were forming an alternative government, and that Boris Johnson and Michael Gove were going to be head of it. This transformed the issue of Vote Leave into one of politicians usurping power, which is something the press cares about a lot more and is willing to cover. And, when Cummings got Johnson and Gove to discuss the reasons why they were forming an “alternative government”, namely the same focus-tested issues from before, this allowed those issues to get press coverage.

EA politicians need to do something similar. Carrick Flynn accidentally found out how the press worked when by far the biggest story of his campaign was a mysterious young crypto billionaire giving him $7 million, followed by environmentalist groups condemning him for his owl remarks. Or, in other words, money and interpersonal drama.

If EA groups or Carrick Flynn had planned better, they perhaps could have manipulated the press to their own benefit. For example, Carrick Flynn and Sam Bankman-Fried could have collaborated to make the story more like Flynn convincing Bankman-Fried to invest $7 million into Oregon as a green job initiative as part of some nonprofit that Flynn set up. That would require some extra work, but would have played way better in the press.

To conclude, I don’t mean to denigrate Carrick Flynn, EA, or Sam Bankman-Fried. This criticism comes out of a place of love, as I really do appreciate what EA does, what it stands for, and the impact it’s had in my life. I also think that Carrick Flynn seems like a great, hard-working guy, and I have no doubt he’d be the same as a politician.

However, as I said in the beginning, $14 million is a ton of money, whether you measure it by bednets or Congressional race standards. Dominic Cummings ran a nationwide campaign with about the same amount of money. If EA can’t win a local Congressional race with that amount, then there needs to be some serious reworking of how we think about things. I’m hoping this will be a good place to start.