In my corner of Twitter, I frequently see science-adjacent material posted by science enthusiasts. Tweeters grab provocative graphs or abstracts from the scientific literature and post them uncritically. Then, a bunch of other reply people talk about how amazing/terrible/interesting the results are, again uncritically.

There’s nothing wrong with this, per se, but there’s not a lot right with it either. It all goes part and parcel with Twitter as a place where our emotions are briefly and intensely aroused, then dismissed, with only a faint memory to indicate why we ever felt so strongly.

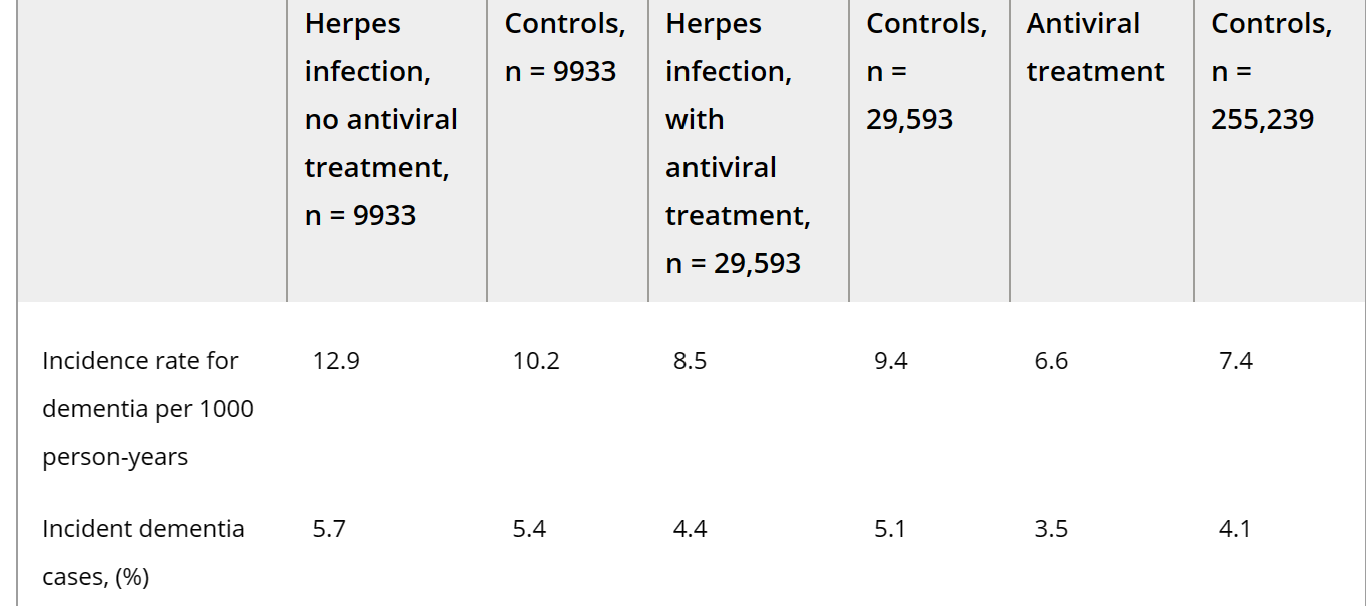

Anyhow, this is the most recent of these that caught my attention. It’s a graph that purports to show herpes causes dementia. It’s from a Taiwanese study that purports to show that the cumulative incidence of dementia from people with herpes is way higher than from people without. It also purports to show that treated herpes is almost as safe as being herpes-free, dementia-wise.

The graph is intentionally dramatic, which is why it went semi-viral on Twitter. But, of course, science isn’t just about dramatic graphs. The data behind the graphs, and how they got that data, is also pretty darn important. So let’s dive into it.

First of all, I didn’t notice until writing this blog post that the Tweeter in question, Cremieux, changed the graph from the paper. Here’s the original graph from the original paper.

Cremieux not only took out the HSV infection line, but he also changed the y-axis from cumulative risk of dementia to cumulative incidence of dementia. However, the original graph is also confusing, and hard to understand how it comes from the data. So, let’s ignore this graph and just go straight to the data, which is the important part.

Let’s start with the obvious thing: where’s this data from? Well, it’s from the Taiwanese National Health Insurance program. They grabbed data of people who were above 50 with newly diagnosed HSV who visited the doctor at least three times for their HSV between January and December 31, 2000 (why those specific dates? Who knows!)

Here’s where I have an issue, though. Herpes/HSV, as you might know, is everywhere. Probably over half of the population over 50 has it, and possibly over 70% in Asia. So, here’s the issue: who exactly is first getting diagnosed with herpes at age 50, and who is so bothered by their herpes at age 50+ that they’re visiting the doctor 3+ times for it?

Well, the two issues are probably linked. We are likely talking about people with the sort of immunosuppression (or other issues) that cause someone to experience their first severe herpes outbreak when they’re 50+, and then be so bothered by it that they visit the doctor 3 more times in the same year for it. We’re not talking about healthy people, in other words.

That same Tweet thread points to similar studies in Sweden and Korea, but those have the same issue. Anyone who’s gone to the doctor because of herpes, especially if they’re looking for antivirals, is not representative of a typical person. Most people have herpes. Most people do not go to the doctor for it. Most people don’t get antivirals for it. So, a real analysis of this study might be something like, “People over 50+ who are unhealthy enough to have herpes that bothers them tend to get dementia”, which isn’t nearly as interesting a result.

That being said, we still have the issue of why antiherpetic medications would bring the dementia rate down. This is especially weird because antiherpetic medications don’t prevent or cure herpes. They reduce outbreaks in most people, but, over a 5 year period, only 20% of people will be outbreak-free for the most common anti-herpetic medication, acyclovir. For context, the Taiwanese study claims a hazard ratio of 0.031 for dementia for patients who take acyclovir for longer than 30 days. That’s a crazy risk reduction assuming these people are still having outbreaks, just less frequently.

In order to explain this, we might take a look at the Swedish study. It claims not only do people with herpes who take antiviral treatment have lower rates of dementia than normal people, but so do people who take antivirals and don’t even have herpes. This raises the possibility that it’s another effect of the antivirals causing the reduction in dementia risk, not the part where it cures herpes.

That would be one explanation as to why a medication that only reduces outbreaks, but doesn’t cure the herpes itself, would be effective against dementia. And it’s certainly possible. Aciclovir, and all antiherpetic medications, are working on some fundamental biological mechanisms in order to inhibit herpes’s replication. These mechanisms might have some effect on dementia.

Or, another explanation for why reducing outbreaks would decrease the risk of dementia would be to stick with an interpretation closer to that of the original study. This would be something like, “Each outbreak of herpes and the associated immune response causes a risk of permanent brain damage by mechanisms such as HSV-1 encephalitis. Suppressing the outbreaks and the associated immune response decreases the risk of dementia. QED.”

Given the data, I don’t think there’s a good way of deciding between the two options presented above. We can either choose:

1. Sick people tend to get dementia, and also maybe antiherpetic medications have a side effect where they prevent dementia, or

2. People with herpes get dementia, and antiherpetic medications help prevent dementia by preventing the replication of herpes.

What would solve this issue? Well, a better epidemiological study, for starters! Let’s take some inspiration on how to fix this from the best epidemiological study I’ve seen in a while, the “Epstein-Barr virus causes multiple sclerosis study”, which I’ve written up before.

First, in order to fix this study, we’d need to make sure that we’re not just looking at people who are getting diagnosed with herpes for the first time. We want to make sure they’re actually getting herpes for the first time. So a great way to solve this would be to have a big collection of blood samples over a long period of time (e.g. from the same military data as the EBV data) and then test all of those for herpes. Given the prevalence of herpes, a random sampling should do it, and you’ll be able to capture exactly when someone caught herpes, assuming it was after age 18. This test should be a PCR test for the actual viral DNA as well, instead of looking for antibodies.

Not only would that be more accurate, then we’d be able to test our hypothesis of “the immune response to herpes causes dementia”. Because, like our EBV study, we’d be able to test whether developing the antibodies to herpes is associated with dementia. If it is, that supports the idea that the immune system attacking herpes in the central nervous system causes dementia. If it’s not, then we’re going to be stuck without an obvious mechanism, unless it’s herpes itself causing dementia.

We also might be able to stratify the level of antibodies with the risk of dementia. If we can assume that people with high levels of antibodies are actively fighting herpes, and if those people then are more likely to get dementia, we’ll get a pretty clear story on what’s happening.

And then, finally, we’d finally be able to say “herpes causes dementia, and all of us should get on antiherpetic medication when we get herpes”. But until then…eh? I’m not convinced.