Warning: this is long. I originally wrote it for ACX’s “Everything But Books Review” contest. It didn’t make it into the finals, so I decided to write it here.

The three best selling videogame franchises of all time are, in order Mario, Tetris, and Call of Duty. It’s an interesting list, because each of them represents dramatically different visions of what videogames should be.

Mario represents the idea of videogames as light, escapist fantasy. It’s built around lovable, recognizable characters in a brightly colored fantastic world who alternately battle and play with one another. The morality is black and white, the stakes are never particularly high, and the franchise is never too worried to explain why Mario needs to defeat Bowser in combat one game and doubles tennis the next.

Tetris is an abstract puzzle game that comes straight out of the former Soviet Union. It’s the paradigmatic example of videogames as abstract, logical puzzles in the same way that chess or checkers are. There are falling tetrominos (tetra meaning four, and mino from “domino”), and they need to be aligned in a 2d plane by rotating them. The joy of the game comes from shape rotating under time pressure. There are no stories, no characters, and no morals. The only concession to aesthetics is the annoyingly catchy theme song.

Then, there’s Call of Duty. Unlike Mario, a fantastical shell for innumerable types of games, or Tetris, an abstract instantiation of a singular puzzle, Call of Duty is, and has been, an annual, expensive showcase for a “realistic” combat simulator. Each year, millions of Call of Duty players buy the next annual installment so that they can pretend to be grizzled war veterans shooting and being shot by other grizzled war veterans, both computer-controlled and human alike.

Because Call of Duty releases annually, and because it places an emphasis on realism (although never at the expense of fun), it has a unique pressure to be timely in a way that the other franchises do not. In other words, it tries to reflect the world that it was developed in, through the lens of the American developers who guide its development.

The Call of Duty developers have taken this idea of reflection in different ways over the course of the franchise. Some installments of the franchise take this literally, and try to make the plot of the campaign mirror current geopolitical trends with the technology to match. Some installments of the franchise try less to reflect current trends and more to reflect current worries, with narratives of America’s fall and our adversaries’ rise. And many, many installments try to use current sentiments to reflect back on America’s past wars, most often WW2. Never before have so many young men in their basement wasted so much of their time for so little.

All in all, there have been 21 mainstream Call of Duty games, one for almost every year between 2003 and 2024 (2004 being the sole exception). They are an almost continuous, two decade long showcase into how America sees itself in relation to its foreign privileges and obligations, especially its military. It is the single most popular, most commercially successful lens into how America sees itself in relation to the outside world. Given the radical restructuring going on right now of that very subject, it’s worth taking a look back through Call of Duty titles to figure out how we got here.

The first Call of Duty had a simple goal: to make the most atmospheric WW2 shooter ever made. It would be first person; take you on a grand tour of the major WW2 battlegrounds through American, British, and Soviet soldiers; and it would make you feel like you were goddamn Audie Murphy. You’d shoot, throw grenades, lay down suppressive fire, and, unique for the shooters of the time, feel like you were playing a decisive role in massive battles along with your allies. You wouldn’t be a one man wrecking ball like Doom guy or Master Chief, but you would be a hero soldier.

The next two Call of Duty games, appropriately named Call of Duty 2 and Call of Duty 3, were the same but better. In 2, you’d defend Stalingrad as a Soviet private, destroy German tanks in North Africa as a British sergeant, and charge German bunkers as an American corporal. You’d do about the same in 3, but this time as an American private, a British sergeant, a Canadian private, and a Polish corporal in the tank division. Thousands of Nazis would die by your hands by the time the campaigns were done, and your manly comrades would send up virtual cheers for you, assuming they also hadn’t died heroic deaths. Or, you know, you hadn’t accidentally shot them in the back when their AI pathing led them in front of your machine gun.

It was the next Call of Duty, Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, released in 2007, that the developers first considered making a more complicated political statement than “it was good and cool that the Allies won WW2”. This probably had something to do with the times. By 2005, when COD4 started development, it was becoming increasingly clear that, despite what George W. Bush had promised, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were not going to be savior stories. We were 4 years out from having resoundingly conquered Afghanistan and 2 years out from having conquered Iraq and yet, somehow, the wars were still going on.

Worse yet, the people who we were supposed to have saved hated us. I mean, yes, most of Afghanistan had hated the Taliban and an even higher percentage of Iraq hated Saddam, but they also hated the Americans who were bombing their houses and roads. And if America hadn’t found Osama in Afghanistan or WMDs in Iraq, and the people there didn’t want us, what exactly were we doing there? Were we really just there for oil, like our critics said? Did anyone know?

COD4 took that uneasiness and created a world out of it. Gone were the clear lines of good vs. evil of the past. You serve as British and American soldiers in the then near-future of 2011, trying desperately to unravel a tangled web of alliances between Russian nationalists and a Middle Eastern warlord before they unleash Cold War era nuclear weapons . Not only are allies and enemies not who they appear, but your player characters are no longer straightforward heroes. Your characters shoot men in the back, knife them as they sleep, and, in one mission, dispassionately annihilate them from 12,000 feet up in a Lockheed gunship.

Sometimes, your characters fail, too. In the third level, you play as the erstwhile president of Saudi Arabia in the minutes leading up to his public execution. You can only look around helplessly as you’re driven to a stadium, your supporters executed in the street while you watch. Finally, you’re dragged out of the car, tied to a pole, and shot in the head.

Meanwhile, in the 10th mission, your player character, a redblooded American sergeant named Paul Jackson, is taken out by a nuclear strike after a seemingly successful rescue mission. You don’t just play as him as he heroically rescues a stranded pilot from certain doom. You also play as him after the helicopter that was meant to rescue you and that pilot is blown out of the air by a nuclear bomb. Your last few moments as Paul Jackson are spent crawling on the ground, devastation all around you, before you succumb to the effects of radiation poisoning.

War crimes, the uneasy reality of American military superiority in every war we fight, our numerous military failures despite this superiority: this is Modern Warfare. This is what the developers of COD4 felt when they wanted to create a “realistic” war videogame in 2005. And they succeeded. COD4 was by far the most successful entry in the nascent franchise, both in terms of critical success and in sales.

The next installations of Call of Duty took this idea and ran with it. First, Call of Duty: World at War went back to WW2. But this time, it focused on the Pacific theater, famous for its brutal island-hopping warfare. And World at War leaned into the brutality. You start as an American soldier, watching his comrades get tortured and executed by the Japanese on Makin Island. You quickly turn the tide, burning the Japanese out from their bunkers with flamethrowers as they cry out in pain.

By the time you finish playing as American Private C. Miller, you have committed dozens of war crimes and watched dozens more be committed in front of you. This prepares you for the next half of the game, where you play as a Soviet soldier, left for dead in a body-filled fountain in Stalingrad. Your sergeant, played by Gary Oldman (by this point, they had the big budgets to hire star actors), urges you to be as brutal towards the Germans as they were towards the Russians. Across the remaining missions of the game, you wade across a sea of blood as you and your fellow comrades surge towards the Reichstag.

Funnily enough, this push towards reality in Call of Duty also introduced what ended up being another Call of Duty mainstay, a push towards unreality with the zombie mode. Immediately after Private Petrenko plants a Soviet flag on the Reichstag, your next mission begins, as you fight off an endless horde of Nazi zombies with colorful powerups from soda cans. Or, to think about it another way, right Gary Oldman tells you that you need to treat German soldiers as if they’re not human, they literally become zombies with an unslakeable thirst for blood.

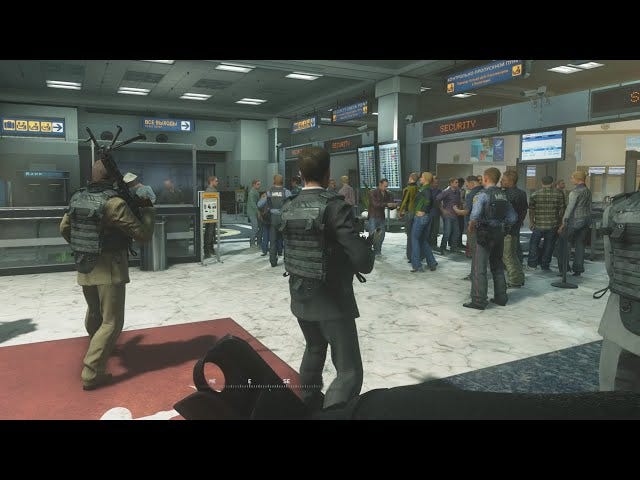

The next Call of Duty, Modern Warfare 2, returned us to the near future, while further venturing into the heart of darkness. MW2 was the first Call of Duty to allow killing of civilians without penalty, in one early mission where you, as a double agent, pretend to be a Russian terrorist laying siege to an airport. You don’t have to kill the civilians in the mission, but the game doesn’t punish you for doing so, and your comrades encourage it. That mission ends with the terrorist leader revealing that he knew you were a double agent all along, shooting you in the head and driving off in order to frame you, an American agent, for the massacre. The intended message: you have betrayed your morals for nothing, and your country will suffer as a result. By the end of the game, this message gets its full weight, as a nuke detonates over Washington DC and an American general reveals he was behind the plot to destroy America all along.

Gamers and critics rewarded the Call of Duty developers for these morally grey storylines with record sales and rave reviews. It was the end of the 2000s in the real world by this point, and the George W. Bush “Support Our Troops” jingoism had been thoroughly replaced by the Obama “Publicly Support Ceasefire, Privately Support Drone Strikes” ruthless pragmatism. For the next few years, Call of Duty expertly rode this uneasy wave, bouncing back and forth between the past and the near future with succeeding titles, this time with the past being not the almost unambiguously good World War II, but the very much morally ambiguous Vietnam War in the bestselling Call of Duty: Black Ops subseries, or CoD:BlOps for a much more entertaining title.

Unfortunately, despite increasing commercial success, it proved surprisingly difficult for the developers to keep their creative momentum. Part of this was the yearly development cycle, although this was now being split among multiple development teams. But part of it was the fact that, while cynicism and moral ambiguity is fun for a while, at some point it gets exhausting. I mean, you can drag gamers to more and more exotic locales to commit war crimes or witness nukes going off in major cities, but at some point they are going to run out of war crimes and you’re going to run out of cities to nuke. After gamers had witnessed the destruction of El Paso, London, Los Angeles, and most of the Middle East and tortured people for information in twice as many locations, they were a bit exhausted and ready for a change.

This change came in 2014, the peak of Obama’s second term. By this point, America was a much calmer place than it had been. We had recovered from the 2008 economic crash, withdrawn from Iraq, and were seemingly about to withdraw from Afghanistan. Our foreign policy was all about limiting engagement while limiting risks. So, we carefully forged treaties with Iran, carefully sanctioned Russia over invading Crimea, and carefully built regional alliances in the Middle East to combat the disturbing rise of ISIS.

Call of Duty read the national mood, as it always did. The developers knew that they couldn’t go back to the joyful warrior idealism of the early Bush years, but they also couldn’t remain in the morally ambiguous muck they had been wading in. So where was there to go? In the words of the immortal Tim Curry in Red Alert 3: SPPPPPPPAAAAAACCCCCCEEEEE!!!!!!

Or, to be more specific, the future, in which space warfare plays a large part, along with exoskeletons and robots. Now, this wasn’t a full rejection of “realism”. The Call of Duty directors didn’t want to do the full space opera of Halo. So, in these next games, there was still the geopolitical machinations that Call of Duty had grown so fond of. But the developers were careful to make sure that they were defanged. This time, it was only the villains who would kill civilians, and this time these villains would be cackling directors of private military corporations who would launch ICBMs from their futuristic bases in New Baghdad. Bond villains, in other words.

I regard this as kind of a drifting period for Call of Duty, like it was for America at large. Since the first Call of Duty, in 2003, America had gone through successive periods of righteous anger, disappointment, disgust, disillusionment, and acceptance. We and our virtual avatars no longer were sure we wanted to be the good guys, but we definitely didn’t want to be the bad guys. We just wanted the world to be calm and nice so we could take a breather, put our head on our desk, and dream of space marines.

Which we did, right up until the Trump years in the end of the 2010s. As it turns out, not everybody was closing their eyes and dozing off. There were a lot of pissed off nationalists, in America and elsewhere, who did not like the slow turn their countries were taking towards liberalism and peaceful globalism. Their energy and anger caught the liberal world order by surprise. Trump jerked the American steering wheel hard towards isolationism, Xi Jinping jerked the Chinese steering wheel hard towards expansionism, and Britain Brexited. Liberals across the world reacted by grabbing the steering wheel and trying to force their countries back even harder towards liberalism. The divisions threatened to pull the countries apart, especially in those countries who lacked the authoritarian decisiveness necessary to quell the liberal protests (i.e. not China).

Suddenly, the world was real again. We were all awake. Some of us were woke. Call of Duty took note. It made a fresh start. Call of Duty: Modern Warfare (2019) came out in, well, 2019. Its story, for the first time in the series, was also set in the same year it came out. It was grounded, too, at least by Call of Duty standards, neither heroic nor cynical. It was about soldiers, doing the best they can, trying to contain terrorist threats in London and Russia. They receive scant support from the governments they supposedly serve. By the end of the game, your characters have a mixed bag of success and failures. Both the US and Russian governments unfairly blame you for your failures, while the British government just tolerates you. You are mostly, but not entirely, alone.

Unfortunately, much like the American government, after this game, the Call of Duty development team splintered in its vision of the world. From this point, Modern Warfare developers Infinity Ward, the first and still primary developers of the game, continued with their fresh, grounded vision of what the world was like now, releasing Modern Warfare II in 2022, with characters grappling with the limitations of American power in a multipolar world.

Meanwhile, Treyarch, who had always been responsible for the continuation and expansion of Infinity Ward’s vision (e.g. Call of Duty 3, Call of Duty: Black Ops), refused to follow Infinity Ward into this grounded present. They continued mining the ambiguous past, their Cold War era plots getting progressively more byzantine until the repeated revelations of brainwashing and sleeper agents made it impossible to tell who the Americans in the story even were anymore.

And lastly, Sledgehammer, the weakest of the development teams, who had always been responsible for the most forgettable of the titles (e.g. Advanced Warfare, WWII, Vanguard), had Modern Warfare III dumped upon them by publisher Activision in the wake of Activision’s acquisition by Microsoft. They reacted by losing Infinity Ward’s thread with these Modern Warfare reboots entirely, releasing a game set in the then-present of 2023 with a plot that might have been morally ambiguous if it had made any sense at all.

And that brings us to the present day. Call of Duty’s reflection of the world, in the year of our Lord 2025, has fractured. It no longer has a single unifying vision, either in time, view of American power, or morality. It’s multi-polared, and gamers can choose which reflection of America best suits their view of the truth: Infinity Ward’s grounded realism, Treyarch’s horrendously complex bombasticism, or Sledgehammer’s loud incoherency.

It’s hard to say what’s next for Call of Duty. Its publisher has been devoured by Microsoft, who are determined to use Call of Duty’s annual releases to push subscriptions to its Game Pass services. The delicate balance of powers between its 3 developers is in disarray, as Infinity Ward’s next project has been pushed back to 2026, forcing one of the other two developers to step up out of turn if they intend to keep up the annual release cycle. But no Call of Duty has been announced yet for 2025, even though we’re a quarter of the way through the year. It might just be that gamers simply can no longer rely on Call of Duty for their annual reflection on America.

Are the gamers of America, and the world, prepared for that eventuality, though? Their view, nay, our view of the videogame industry is centered around this annual release. Since I was 10, I’ve lived in a world in which Call of Duty has reigned supreme among first person shooters. My virtual blood has infused the digital battlegrounds of Call of Duty countless times, and my real-life shooter sweat has infused controllers from my parents’ basement, to my college dorm room, to the succession of apartments I’ve inhabited in my current city.

Sometimes I’ve hated Call of Duty. Sometimes I’ve loved it. Sometimes I’ve felt at home in its view of the world. Sometimes I’ve felt alienated by it. But it’s been a long time since I considered a videogame world without it. Now, I don’t think 2025 will be the end of Call of Duty. It’s too valuable and there are too many people invested in it.

I don’t think that Microsoft appreciated, though, when they took over Call of Duty exactly how complicated it is to develop though. It’s a delicate, complex, massive endeavor that takes place every year. I mean, if you think the above annual creative effort sounds wild, keep in mind that I didn’t even mention the massive and multifarious multiplayer modes and elaborate marketing that is packaged in with every release. There is so, so much work that goes into keeping Call of Duty running. It’s not invincible. It’s entirely possible for Microsoft’s too-clever-by-half meddling to irreparably damage it. And yes, this is a metaphor.

What is this brave new world we’re entering, as our allies become foes, our foes become allies, and we hollow out our most robust institutions from within? I don’t know. Hopefully the next Call of Duty will help me figure it out.