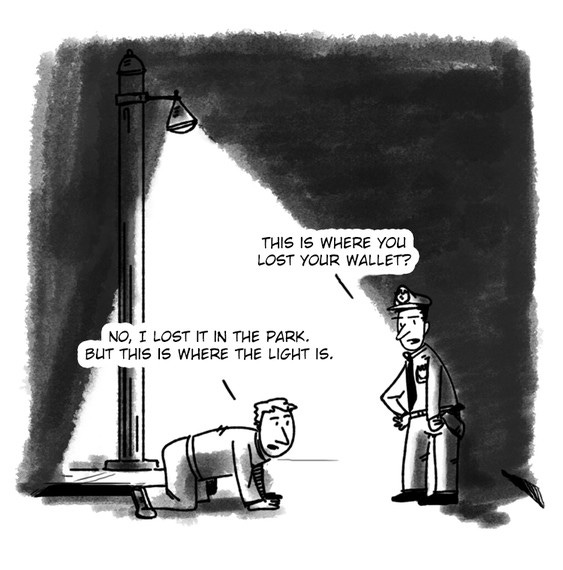

Here’s one of my favorite jokes: a guy is walking home late at night, when he sees a drunk looking in the grass under a street lamp.

The guy asks what the drunk’s doing.

“Looking for my keys,” the drunk says.

The guy takes pity on the drunk and decides to help him look for his keys. They search the grass for about 20 minutes, and finally the guy tells the drunk that he doesn’t think his keys are there.

“Oh, I know,” says the drunk. “In fact, I’m pretty sure I lost my keys about 100 yards up the road that way.”

“What?! Then why are we searching here?”

“Because the light is better here!”

This, in my opinion, is a great joke. First, it’s pretty funny, and the punchline never fails to get at least a chuckle. Second, through its absurdity, I think it actually reveals something pretty profound about human nature.

Whenever we look for anything, we look under the light. We have to; there’s no other option. We do that even if we know that under the light isn’t the best option, or maybe even if we know that under the light isn’t a good option at all. We end up wasting so much time this way, and yet we do it again and again.

Let me give an example from my own line of work, biotech. I was talking to someone the other day about using calcineurin inhibitors for neurodegenerative disease. This is something I’ve thought a lot about: my own company’s drug is a calcineurin inhibitor, and curing neurodegenerative diseases is a major goal of mine.

This guy I was talking to had been working on calcineurin inhibitors for a long time, at least 20+ years. I was eager to learn from him.

“You know,” he said, “if calcineurin inhibitors are going to work for any neurodegenerative disease, it’s Parkinson’s.”

“Really?” I said. “I’ve looked into it, and it really doesn’t seem like Parkinson’s pathology has anything do with calcineurin. There’s also no clinical evidence that it would have any effect, at least as far as I know.”

“Yeah, but Parkinson’s has alpha synuclein as a biomarker. You can measure it.”

And that was it for him. That was the crux of the issue. He didn’t think about whether Parkinson’s was the neurodegenerative disease where he was going to find his metaphorical keys, he just knew that the light of a biomarker was there.

I see this pattern of looking where the light is again and again in the sciences. Early on in Covid, I found myself immensely frustrated by “experts” in epidemiology whose entire field was based on incredibly simple models of disease spread that didn’t even take into account the biology of the disease (e.g. whether it was airborne or spread through surfaces). Somehow, they had all gotten PhDs without ever even considering whether their models could be empirically validated.

But, of course, they couldn’t empirically validate their models, at least not before Covid. It was impossible to empirically validate a model about the spread of a pandemic, because there was barely any evidence to do so. But the field still needed to justify its existence and publish its papers, so they published their papers where the light was: computer models simple enough for an academic to tweak and run. Then, they convinced themselves (and a big part of the rest of the world) that’s where their keys were, too.

Examples abound elsewhere, too. In the startup world, so many startups try to address the problems of the most visible businesses (e.g. restaurants), even though those businesses are often a terrible market. Or, in the public policy world, hundreds of millions are spent on trying to help the small minority of visibly homeless people, and almost none on the vast majority of homeless people who are sleeping in their cars or on friends’ couches and trying not to be publicly known.

Everywhere we look, we look in the light. And if what we’re looking for isn’t in the light, and we refuse to bring a flashlight, we’ll waste our time searching the grass as surely as the drunk in my joke.