Feb, 2023

There’s been some exciting updates recently with my biotech/pharma startup, Highway Pharmaceuticals. Along with finally making a first inroad with the FDA and almost finishing our pilot trial (despite some hiccups along the way), we’ve also identified a contract development and manufacturing organization, or CDMO, and signed a proposal to manufacture the drug.

The short version is that manufacturing the drug will take $300,000+ and more than 7 months1, plus 24 months of testing at the end of it. At the end of the 7+ months, we’ll have a batch of actual drugs suitable to be given to actual cats for safety testing. At the end of the 24 months, we’ll have a recipe for a drug that’s suitable to being put on the shelf of your local veterinarian pharmacy, assuming FDA approval.

Neat, right? But also, wow, that’s a lot of money and time! What goes into all of this? Why is this so complicated, considering we’re just taking old drugs, combining them, and putting them in a new capsule?

These are the questions I had before I started all of this. To be honest, this is my first time manufacturing anything physical. I’ve self-published books and made an app, which have their own headaches, but nothing like this. I’ve had zero experience with what it’s actually like to get something physical out into the world, and now I’ve jumped into the deep end with one of the most regulated and complicated categories of products known to man.

And deep this end is! Through conversations with my manufacturing consultant and the manufacturers, I’ve learned a lot about just how complicated manufacturing drugs is and where all the money and time goes. To continue the analogy, while I still certainly don’t know how to pilot the submarine into this deep end, at least now I understand why the submarine has so many buttons. And I believe that the consultant and I have identified a solid captain (CDMO), although we will still keep a close watch to make sure they’re not sailing into any reefs.

So, here are the broad steps needed to actually make a drug with a CDMO.

1. Obtain the API.

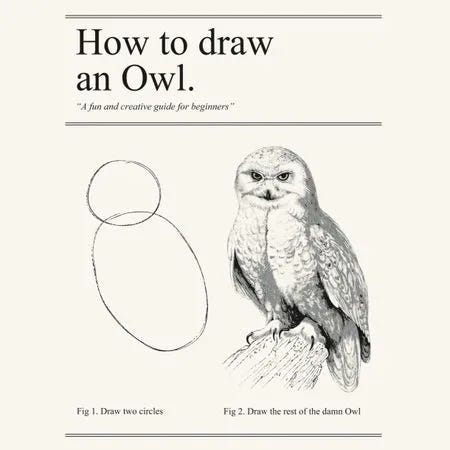

Manufacturing a drug starts with already having the active pharmaceutical ingredient, or API. This is the part of the drug that actually does the work (i.e. the thing on the back of the package, like “acetaminophen” or “sildenafil”). This is kind of a copout, as this is obviously the most important part of a drug. You might see this as a “draw the owl” sort of deal.

And it kind of is. But, an API does not a drug make. Yes, the active ingredient in Tylenol is acetaminophen. But, if you buy that API directly, you are going to get a kg of powder and it will run you about $4500. This will not be helpful to fix your headache.

A CDMO’s job is to turn that API, in whatever form it comes, into a drug that can be put on a pharmacy shelf and then sold to an end user. The API can come in a lot of different forms and the end user’s drug can come in a lot of different forms, so CDMOs frequently have specializations like “liquids” or “inhalants”.

Our drug is two powders that we intend to combine into a liquid softgel, so our CDMO’s job is to find a way to take two powders, dissolve them into a liquid, and put them into a soft gel capsule. Not coincidentally, this is now my specific experience with CDMOs, so it’ll cover the rest of what I discuss in this piece.

Now, before a CDMO can combine two APIs into a single liquid softgel, though, they need to actually get the APIs. That’s the pharmaceutical company’s job.

If we were a traditional pharma company, we’d likely have some sort of manufacturing facility that makes the API, which is a multimillion dollar investment in and of itself that comes with fifty times the amount of headaches, not to mention the FDA inspection. Meanwhile, if we were a traditional startup making a new chemical entity, we would have already hired a contract API manufacturer, which ends up being a really complex, expensive relationship with a factory in which you make small batches of a highly specialized product. Scientifically, I’d estimate that this is approximately twenty times the amount of headaches.

But, fortunately, we’re a repurposing startup, which means we get the API by calling up generic manufacturers and asking them how much they charge per kg of the API. Once they tell us, we work together with the manufacturer to fill out the standard safety data sheet and importation forms to get the drug across borders and safely into our CDMO’s factory.

Then, of course, we have to coordinate the API manufacturer and the CDMO to make sure they actually do ship the API in the right way, at the right time, to the right place. This is about one headache’s worth of work, although it’d be more if we were working with dangerous substances or controlled substances (i.e. APIs that people can use to get high).

One of our big concerns about shipping the API in the right way is to make sure both the generic manufacturer and the CDMO knows which part of the API is GMP and which part is not, and not to mix up the two. Now, you’ll have to forgive me for introducing yet another acronym (technically an initialism), but this one is important and will come up again. Allow me to explain it, if you would.

GMP stands for “Good Manufacturing Practice”. You might notice that this is a noun, and not an adjective, so it doesn’t really make sense to say “This active pharmaceutical ingredient is good manufacturing practice”. But, we’re going to just have to let that go and accept that GMP is most commonly used as an adjective to describe a certain set of standardized, highly documented manufacturing practices.

GMP status is important because any drug that goes into an official FDA trial or into an end user (i.e. a person or a pet) needs to be produced under highly documented, standardized manufacturing practices. This is for both safety and traceability if things go wrong. Because of all the extra work that goes along with producing them, GMP drugs are always more expensive than their non-GMP equivalents.

But, if we want the finished drugs that come out of this manufacturing run to be used in our safety trials (which is literally half the reason we’re doing this manufacturing run), we need to be using GMP drugs. The only reason why part of the API we’re ordering is non-GMP is that we also need to produce a prototype batch of drugs to test our process before making an actual batch of drugs. We’ll just be throwing out the prototype batch once we’re done, so the API doesn’t need to be GMP.

Anyways, let’s say that you do all this successfully: the paperwork, the logistics, the payment. Now, at long last, you can actually start employing the CDMO.

2. In which the CDMO just keeps testing.

So, we have two powders. We want to combine them into a liquid. What do we do?

Well, it’s pretty obvious. We mix the powders together and add some sort of liquid that will dissolve both of them (the “excipients”). Ta-da!

Of course, like all things pharma, the devil is in the details. We need to test to make absolutely sure that this liquid:

a) Completely dissolves the APIs

b) Keeps the APIs dissolved

c) Doesn’t make any chemical changes to the API

We will be testing this over, and over, and over again. So, once we identify the excipients, we dissolve the powders, and test. Then we identify a capsule shape and size, practice mixing all the ingredients together and filling the capsule, and test. Then we manufacture a full prototype batch with exactly the same steps and ingredients we’d use for an actual batch, and…. test!

This third test, however, is a little more exciting. Instead of testing immediately after we produce the batch, we put the prototype batch through a range of temperatures and humidities for a full 6 months, trying to replicate the full spectrum of what it might experience on a pharmacy’s shelf in winter or in summer. Then, once again, we test.

3. Keeping busy.

Of course, we don’t want to be just sitting on our hands while we’re waiting for this prototype batch to finish 6 months of testing. That’d be a waste of time.

So, instead, we figure out everything around the manufacturing that isn’t directly involved with making a batch. Namely, the cleaning, the assay, and the method validation.

Cleaning is exactly what it sounds like. We figure out how to clean the machines in between batches so they’re ready for the next one. If this weren’t pharmaceuticals, this probably wouldn’t have to be a separate, costly step. It’d probably just be a post-it note next to the cash register or something, along with a reminder to get more Clorox.

But, because these are drugs that are going inside sick patients, we’ve got to be a little more intentional with our cleaning. Every part of the cleaning process is prodded and examined: what we use to clean (the “cleaning matrix”), what our cleaning procedure is, and how clean is clean enough (the “allowable residue limit”).

Once we know how we’re going to clean, we next need to know how to make sure the cleaning hasn’t affected our end product. So, we develop an assay to test the drug to make sure it’s exactly as it should be and hasn’t been changed chemically.

Finally, we need to prepare for our GMP manufacturing of our actual drug batch. This means “validating the method”, or turning the steps we figured out during our prototype batch into a formal procedure that can be replicated. This is assuming, of course, that our prototype batch went exactly to plan.

4. Manufacturing the drug.

Finally, at the 6 month mark, we check that our drug still is fully dissolved and unchanged chemically.

Assuming that it is, we can go ahead and manufacture our first batch of drug for our safety trials and our formal, FDA-mandated testing. This manufacturing is GMP, which means it needs to follow the method we developed before and be exhaustively documented. It also means that we need to test the drug again to make sure it was developed right and we didn’t introduce any impurities.

At the end of all of this, we have our GMP batch. This is the batch we will then use for our safety trial, making sure the cats don’t get sick when we give them the drug.

And, importantly, we’ll also use this batch for our…drum roll please…additional testing! This one is the official, FDA mandated test, during which we keep the batch for 24 months at a range of temperatures and humidities and then test it to make sure it’s fine. Practically speaking, we already did that, because a drug that’s stable at 6 months will almost certainly be stable at 24 months. But, good luck convincing the FDA of anything “practically speaking”.

At the end of this 24 month period, as long as you’ve successfully completed your safety and pivotal trials, you have a drug. Huzzah!

Sorry for being vague, but I’m under an NDA. This was the minimum cost and minimum amount of time from the proposals we received. The actual cost and actual amount of time is somewhere north of this.